In many ways, the global markets are in

uncharted waters with no clearly defined swim lanes. These extremes are

forcing many investors to face uncomfortable questions (e.g. what discount rate

should I use in my discounted cash flow analysis?) and feel pressure to

compromise their valuation assumptions and discipline in order to find

investible stocks.

Our predictions are no better than

yours, but holding a little extra dry powder in such abnormal times provides

some comfort and optionality for opportunistic buying if the future surprises

to the downside. Swim carefully, my friends.

Global

stock markets are generally at or near all-time highs:

The S&P 500 is at an all-time high:

Japan’s Nikkei 225 index has gained

more than 25% over the past year to approach a 15-year high:

The FTSE 100 index is also at an

all-time high:

Global

bond yields are near all-time lows:

In the US, the 10-year treasury yield

has drifted down from 3% in early 2014 to 2%:

Turning to Japan, we see a similar

story:

In Germany, the 10-year treasury yield

is at a 5+ year low:

Finally, Switzerland’s 10-year yield

actually dipped into negative territory earlier this year and sits just above

0% today:

Lower rates around the world are

forcing many income-seeking investors to chase yield in riskier, less familiar

markets. For example, according to a recent Wall Street Journal

article,

junk-rated companies have raised over $20B of bonds so far in 2015, more than

double the amount in the same period last year.

The knock-on effects are highly

uncertain but are (at least temporarily) helping riskier firms raise financing

with ease. Do European high-yield bonds really offer value? Only time will

tell.

Commodities

are tumbling: Bloomberg’s commodity

index tracks 22 raw materials and has now declined for four straight years to

sit at a 5-year low.

FX volatility

is increasing: the US dollar has

strengthened significantly since the summer of 2014 and sits near a 5-year low.

The chart below shows the EUR to USD

exchange rate. The rate plummeted to over a 10-year low as the market digested

news that the European Central Bank will introduce a $1.23 trillion stimulus

plan.

Meanwhile, Japan’s yen has declined

more than a third against the US dollar since Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo

Abe took office in December 2012 and began implementation of monetary and

fiscal stimulus. The chart below shows the impact on the yen to USD exchange

rate:

Global

central bank interest rate cuts and stimulus are at unprecedented levels:

Central banks around the world are

playing “currency roulette.” According to Bloomberg, 19 of the 53 central banks

it tracks have dropped their benchmark interest rates in the past three months

– “Low rates encourage consumers to borrow and spend, increasing domestic

consumption. They also devalue currencies, making exports cheaper. That’s good

for the countries selling but hard on countries flooded with cheap products.”

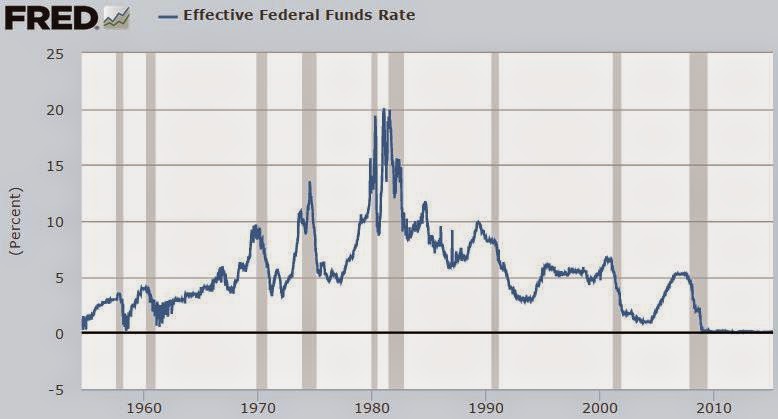

In the US, the federal funds rate

(below) is the interest rate at which a bank lends funds maintained at the

Federal Reserve to another bank overnight. The higher the rate, the more

expensive it is to borrow money. Since it is only applicable to very

creditworthy institutions for extremely short-term (overnight) loans, the rate

can be viewed as the base rate that determines the level of all other interest

rates in the U.S. economy. As seen below, the Fed has maintained an interest

rate of approximately 0% for the last five years, the lowest rate in over 50

years.

Switzerland provides a final example of

the extreme interest rate levels maintained by many central banks. In January

2015, Switzerland stunned global financial markets by slashing its official

interest rate to -0.75% and foregoing its attempts to cap the franc’s exchange

rate against the euro. No central bank has ever

set its official interest so low.

In addition to rate cuts, central banks

have engaged in extreme bond-buying. The Wall Street Journal provided the

following chart:

While the US ended its bond-buying

program in October 2014 (it started in November 2008), the European Central

Bank is just getting started. Starting in March 2015, the European Central Bank

will buy $68 billion of government and corporate bonds each month at least

through September 2016 (a €1tn round of quantitative easing), designed to make

loans and exports cheaper so companies can hire and expand.

Japan’s most recent quantitative easing

program began in April 2013 with plans to unleash a massive program worth $1.4

trillion. Under the plan, the Bank of Japan vowed to buy $70 billion of

government bonds each month using electronically created money. In October

2014, with inflation worryingly low and consumer spending floundering, the Bank

of Japan revealed plans to increase its buying from ¥60-70 trillion a year

previously to ¥80.

The jury is still out on the

effectiveness and knock-on effects of quantitative easing, but here is a

3-minute article by the Economist about quantitative easing: link.

Global

debt-to-GDP has skyrocketed:

According to a report by McKinsey, total debt worldwide

(includes government, corporate, bank, and household debt) has risen by $57

trillion since the end of 2007, representing 286% of global economic output in

2014 compared to 269% in 2007.

The Telegraph provides a longer-term ratio of

global debt (measured differently than McKinsey) to GDP:

Source: The Telegraph

What now?

We have witnessed six years of mostly coordinated global monetary

stimulus. What happens if / when major countries run out of monetary ammunition

before global economies and inflation expectations improve? How will the exit

from global stimulus play out? What happens to government debt payments if

interest rates rise? Will inflation or deflation be unleashed? We do not know,

but we are certainly living in interesting times that will one day make for a

great case study, good or bad.

No comments:

Post a Comment